Addressing Climate Emotions as Part of Farmer Mental Health

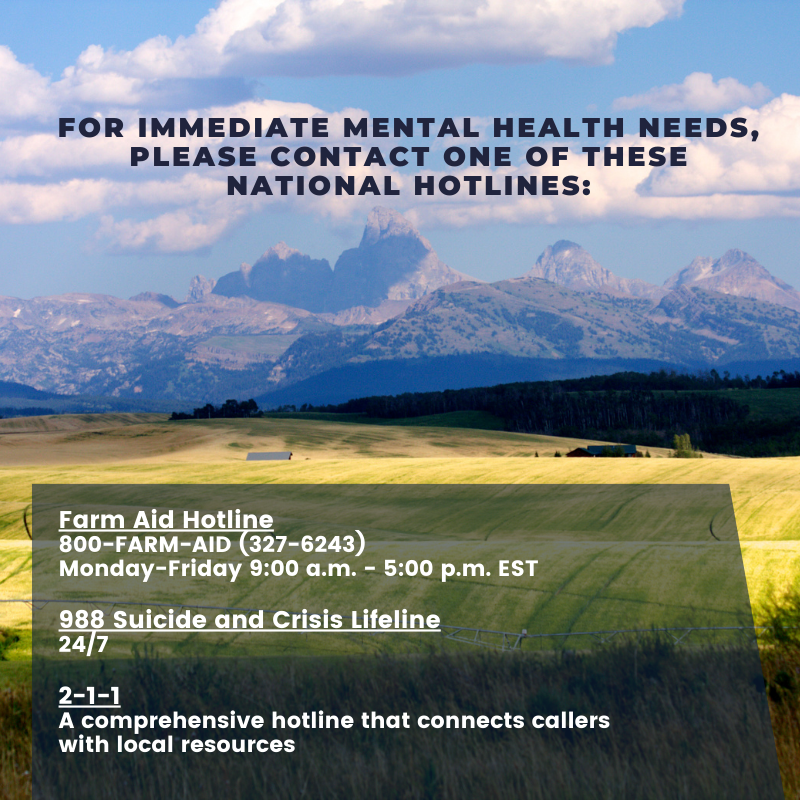

Be advised that this post contains explicit mention of mental health challenges. Please take care of yourself accordingly.

“We count our blessings every day. And yet to know that the work we’ve done . . . the lengths we’ve gone to collect and store water, is simply not enough to shield us from climate collapse, is both heartbreaking and terrifying. We are left with existential dread and anxiety. We are left with the difficult question of, where to call home?” – Maud Powell.

Ecological Grief. Eco-anxiety. Climate Grief. Climate distress. Though they differ slightly, the terms all refer to the set of emotions that arise upon witnessing or learning about environmental destruction or loss, often tied to our experience of extreme events (e.g., flooding, fires, drought). These emotions are receiving increasing attention from writers, leaders, teachers, and mental health professionals across the globe, and they deserve attention from the agricultural community as well.

Researchers have been tracking opinions about climate change for decades, and increasingly, the focus is on emotional and farmers’ mental health responses to climate change. According to a 2022 Yale University Study, Climate Change in the American Mind, most Americans (64%) say they are least “somewhat worried about climate change. Three in ten (30%) say they are very worried. About half say they feel “sad,” and four in ten say they feel “afraid” or ‘angry” when they think about climate change. What these numbers tell us is that – without necessarily having the words to describe it – many Americans are experiencing some version of climate-related stress and grief.

But what about farmers specifically?

In 2020, the national suicide average was 14.1 per 100,000 people (1 in every 7,092 people). The rate for farmers, ranchers, and ag managers was 43.7 per 100,000 (1 in every 2,288 people), the 6th highest rate among occupation groups. Why are producers so susceptible to mental health challenges? Farming and ranching frequently involve high levels of stress, low margins, unpredictability (especially with the weather), debt, physical injury, and isolation. At the same time, they may live in rural communities that lack access to mental health services, and they may perceive social stigma around seeking help.

While there is some research specifically on the mental and emotional impacts of climate change on farmers outside of the U.S., unfortunately, there is almost no research on American farmers’ mental health and emotional experiences of climate change.

We do know that farmers, ranchers, and other food producers are uniquely susceptible to climate-related stress, anxiety, grief, and trauma due to their proximity to and entanglement with the natural ecosystems and weather patterns. They observe shifts because they are outdoors much more than people who work indoors or aren’t actively involved with the life cycles of plants and animals. They observe firsthand the effects of the changing climate on those systems. They have deep connections to the land and to places that may be impacted by climate shifts and climate-related natural disasters. But for the same reasons mentioned above, they may have less access to, or be less likely to seek, support for the mental health impacts of this stress and may be caught up in the immediate economic stressors associated with experiencing extreme events.

Reckoning with climate emotions is about reconnecting to the reality that climate change is real; it is already changing the way we farm and the way we live on planet Earth.

We need to acknowledge that there is emotional pain associated with these changes that all of us are experiencing. In agriculture, some changes may lead to some new opportunities (e.g., Oregon winegrape growers might be able to grow interesting and profitable new varietals), but many of them will be deeply damaging (e.g., smoke impacts to crop productivity and farmworker health), and will be felt unequally across our country and farmers/ranchers/farmworkers and those who tend the land will bear the brunt of it. As agricultural service providers, we are grieving alongside these land stewards as we find a new way to meet our current reality and find ways to foster resilience. Sometimes, fostering resilience means acknowledging our grief and our pain so we can find a way through it.

Here at AFT, we are adapting our work to better address the emotional needs of farmers and service providers we work with. We hope to integrate this approach into our Advancing Water Resilience in the West project to better thread the needle between climate adaptation work on the farm, and the emotional and cognitive work farmers can do to foster greater individual and community-scale resilience. We can’t do the work of climate change adaptation in a vacuum; we need community and resources to support our collective grieving and our collective desire to take action that might improve farm-scale resilience. This notion of resilience would have mental health, which includes an acknowledgement of climate grief and its impacts at its core.

In the wise words of poet Andrea Gibson,

“A difficult life is not less

worth living than a gentle one.

Joy is simply easier to carry

than sorrow. And your heart

could lift a city from how long

you’ve spent holding what’s been

nearly impossible to hold.

This world needs those

who know how to do that.”