Massachusetts Cranberry Producers Find Opportunities for Water Conservation

The following is a blog post series highlighting AFT’s NRCS Conservation Planners. These planners work through NRCS to support Massachusetts cranberry producers for water conservation.

Cranberry farming has been an integral part of the Massachusetts agricultural landscape since the Mid-1800’s, and according to the University of Massachusetts Cranberry Station there are over 14,000 acres in cultivation today, making Massachusetts second in the nation for cranberry production. The cranberry is a native American perennial vining fruit that thrives in the special combination of soils and hydrology found in the wetlands of Southeastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod and islands.

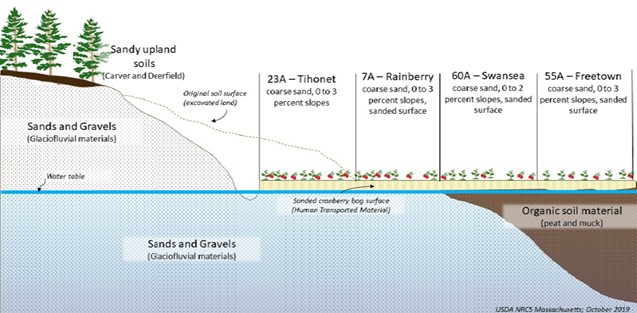

If you’ve visited Southeastern Mass, you’ve likely driven past a cranberry bog and may not have noticed. Bogs contain the ideal soil for cranberry production because of the alternating layers of sand and organic matter. Natural Massachusetts bogs developed thousands of years ago from glacial deposits that were left in kettle holes lined with impermeable materials. Over time these kettle holes filled with organic matter and water thereby creating the ideal natural habitat for cranberries. In order to maintain the productivity of bog soils, cranberry farmers aim to apply sand onto the bog surface every 2-5 years. This creates a layer on top of the accumulated dead leaves and builds richness and biodiversity. Unlike in many agricultural soils where annual crop production is conducted, cranberry bog soils do not require tilling and therefore remain undisturbed.

Growing cranberries commercially requires the support of a surrounding network of forests, ponds, and streams that constitute the wider cranberry wetlands systems. Cranberry farmers in Southeastern Massachusetts own over 60,000 acres of upland habitat that is associated with these cranberry wetland systems and these uplands can be maintained or enhanced to provide habitat for native flora and fauna.

In my role at American Farmland Trust, I work with NRCS to provide conservation planning assistance to farmers and landowners in Massachusetts, specifically those who are based in Bristol, Norfolk and Plymouth County. Prior to joining AFT, I had never stepped foot on a cranberry bog and was in no position to be providing technical assistance to cranberry growers. Luckily for me my NRCS field office in Wareham is comprised of conservation planning staff, engineers and soil scientists who have extensive experience working with cranberry growers to assist them in carrying out conservation projects at their sites. Additionally, I have been taught so much by each cranberry grower that I’ve worked with and they have all confirmed the idea that there are “no bad questions” – the best way to learn is to spend time in the field.

For decades cranberry growers have worked with NRCS staff and local conservation districts to address resource concerns associated with their cranberry bogs and adjacent land. Growers may seek technical assistance to address inefficient irrigation systems, implement plant pest management systems, improve water quality as they circulate water throughout their bogs, and enhance forested upland habitats that surround their bogs. These resource concerns can be addressed in conservation plans, which can accompany applications for NRCS financial assistance programs that help offset the costs associated with implementing conservation practices such as the installation of a new irrigation sprinkler system or increased scouting for insect pests to aid with pesticide application rates and timing.

Climate change has impacted agriculture throughout the United States and the cranberry industry has felt the burden of these changing weather conditions. Increased extreme heat (number of days above 900 Fahrenheit), warming winter months with less ice, and severe fluctuations between heavy rain and drought are taking a toll on cranberry crops throughout the region.

Many Americans understand how important it is for agricultural producers to have adequate water for tasks such as irrigating crops or livestock watering; the importance of water accessibility for cranberry farming cannot be understated. Cranberries are a wetland-adapted plant and commercial cranberry farming seeks to mimic these natural wetlands processes while controlling several variables that are necessary to maximize production. Adequate water is essential for two main aspects of cranberry production – irrigation and flooding.

Sprinkler irrigation systems protect the crop during intense summer heat. This is crucial for allowing the plant to first develop a proper ‘fruit set’ during late June and early July while facilitating adequate growth during the following 3 or so weeks. Growers run their sprinkler systems to provide frost protection to their crops when the plants are susceptible to temperatures below freezing. Growers are worried about frost temperatures during the spring when the terminal buds break dormancy and new leaves and flower buds begin forming, and the fall where fruits are maturing and are getting ready for harvest.

There are three types of flooding techniques:

Winter Flooding: This is done to protect the crop during its dormancy period from ‘winterkill’, which refers to the injuries that cranberry vines can sustain during severe winter weather, and is accomplished by flooding the bog with 8 – 12 inches of water and holding it anywhere from December 1st – March 15th

Late Water Floods: This is where growers withdraw the winter flood in mid-March and then re-flood in April for around 1 month to provide spring frost protection and some additional pest control.

Harvest floods: These that take place in the fall where the bogs are flooded with a foot of water, which allows the fruit to float to the surface where it is then mechanically harvested.

Generally, a grower will use approximately seven to ten feet of water per acre to meet all production, harvesting, and flooding needs. But growers often conserve water by improving their irrigation systems and capturing excess flood water for future re-use. This can be done by installing new irrigation systems that are outfitted with pop-up headers that apply irrigation water and pesticides more uniformly. They can also retrofit their irrigation systems with automation which allows them to remotely run their irrigation pumps based on soil moisture data (beneficial during summer heat) or temperature probes (useful for monitoring frost conditions).

Growers have also constructed tailwater recovery ponds which capture excess water from rain, applied floods events, or irrigation runoff. Capturing excess irrigation runoff is beneficial after pesticide application because the water can be held for a recommended period in order to break down before being released downstream. These tailwater systems create a closed-loop system where the grower can reduce the amount of water removed from the wetland system by capturing excess water and cycling it back through the bogs when needed.

These adopted management practices build resiliency in these cranberry bog systems and allow Massachusetts cranberry producers water conservation to sustain the natural resources that facilitate their crop production and should enable them to continue farming in the face of challenging times ahead.