Digging Deeper into Conservation Matters for the AMP Initiative

This second analysis was produced by AFT’s Water Initiative Director Michelle Perez, Research Scientist Jennifer Tillman, and Conservation and Climate Policy Manager Samantha Levy. Additional research and analysis were provided by Robert Parkhurst and Rebecca Wright of Sierra View Solutions.

In our first article of this three-part series, we focused on what we call, “The Big 3” soil health practices: Cover Crops, Reduced Tillage or No-Till, and Nutrient Management. These were the most popular farm conservation practices selected by the Partnerships for Climate Smart Commodities (PCSC) projects and we expect they will also be selected by the projects under the new Advancing Markets for Producers (AMP) initiative.

We also reminded everyone that conservation professionals have for decades been designing farm conservation practices to support producer profitability and to address resource concerns in the categories of Soil, Water, Air, Plants, Animals, and Energy or SWAPA-E for short. This holds true for practices that have been called “climate smart”– they’re good for so much more than just the climate!

In this second article, we dig deeper into one way of quantifying how well practices address the SWAPA-E resources concerns. We turn our attention to another set of three practices: Tree/Shrub Planting, Prescribed Grazing, and Conservation Cover, since they offer the most “potential total conservation benefits.” Because of that, we hope the AMP projects invest in these practices, too! We explore the “potential total conservation benefit” by using the rating system that signals how well the conservation practice can address each resource concern via the Conservation Practice Physical Effects (CPPE) scores. And finally, we provide details about the CPPE scoring system after we introduce the three practices of interest below.

Definitions and examples

Before we get into why Tree/Shrub Establishment, Prescribed Grazing, and Conservation Cover receive such high CPPE scores, here are definitions and examples of these practices so you can become familiar with them.

Tree/Shrub Establishment: Establishing woody plants by planting, direct seeding, or through natural regeneration. This practice supports other practices that require trees and shrubs to be established, such as Silvopasture (381), Windbreak/Shelterbelt Establishment and Renovation (380), and Riparian Forest Buffer (391). However, for our purposes here, we will stick to tree/shrub establishment that would not also be considered another practice.

o Example: Improving habitat for wildlife and pollinators by planting a variety of species of flowering trees and/or shrubs that bloom at different times throughout the year. This can also provide consistent food for managed bees, meaning more honey for us!

o Example: Planting trees in a pasture to provide shelter and shade for livestock, which can reduce the effects of heat stress on the animals.

Prescribed Grazing: Managing vegetation with grazing and browsing animals to achieve specific ecological, economic, and management objectives.

o Example: Adopting rotation grazing practices by installing electric fencing to divide large pastures into many smaller paddocks, allowing animals to rotate between paddocks so the pasture can rest between grazing. Pastures that are not over-grazed, have time to rest, and have manure evenly spread across them can be more productive.

o Example: Minimizing grazing when soils are wet and prone to compaction; designating areas for use during adverse conditions to protect the integrity of the soil. Overall, this can help improve the productivity of pastures, meaning more feed for livestock.

Conservation Cover: Establishing and maintaining permanent vegetative cover.

o Example: Allowing native vegetation to grow in the alleys of an orchard, instead of maintaining bare alleys, to provide habitat for beneficial insects (which can reduce the need for pest management) and reduce dust during tractor operations (better for human health).

o Example: Planting permanent grasses along a field edge that’s near a stream to prevent soil erosion from degrading water quality and provide habitat for wildlife such as pheasants.

In a nutshell, producers and their technical service providers can design these practices to effectively address the specific resource concerns occurring on site while improving the farm operations’ productivity, soil health, biodiversity, and more.

What you need to know about CPPE

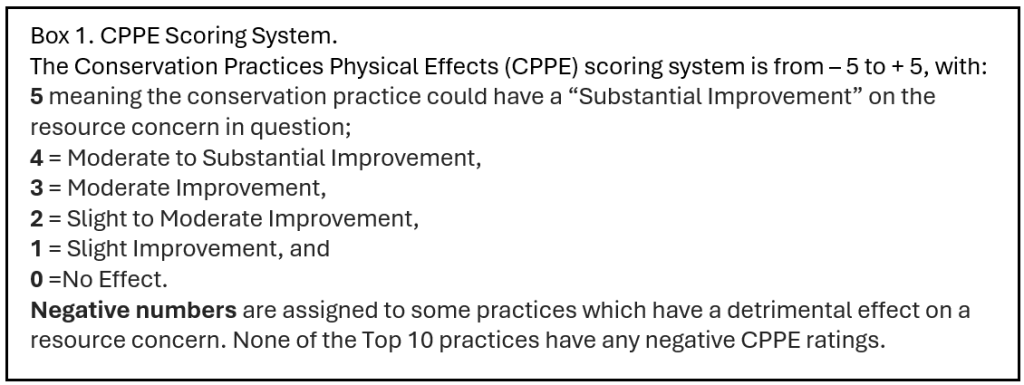

The Conservation Practice Physical Effects (CPPE) tool provides qualitative descriptions and assigns -5 to +5 points to rate how well each conservation practice can address 47 SWAPA-E resource concerns (See Box 1). A high positive CPPE score indicates the practice has a potentially substantial and positive “physical effect” on that specific resource concern.

We’ve used this tool to calculate the sum within each SWAPA-E category, as well as the overall sum across all SWAPA-E categories. A high total CPPE score (within a SWAPA-E category or across all categories) indicates the practice can be expected to have a substantial improvement on a few resource concerns, a slight improvement across many resource concerns, or some combination of the two.

Potential Total Conservation Benefit

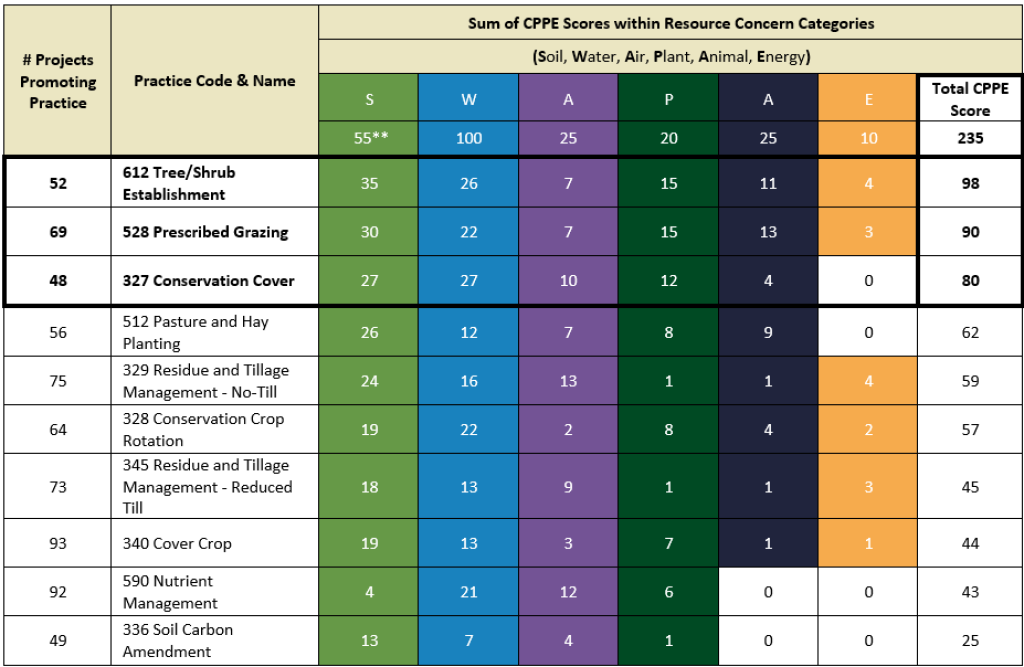

Below is a replica of the table we presented in our first article, but this time the practices are ordered not by the number of projects that selected them but by the highest total CPPE scores. We’ve also included the sum of the CPPE points within each of the six resource concern categories (see Table 1).

* Top 10 most popular practices refers to all the practices selected by the most projects under the initial Partnerships for Climate Smart Commodities (PCSC) initiative, which included 135 projects.

** The top row shows the total sum of CPPE scores that each practice could conceivably earn. For example, the Soil category has 55 possible points because it is comprised of 11 soil-related resource concerns, and CPPE score ranges from – 5 to +5, so 5 times 11 equals 55.

See that Tree/Shrub Establishment, Prescribed Grazing, and Conservation Cover offer a whopping 98, 90, and 80 total CPPE points! Meaning, they can address so many resource concerns and do it so exceedingly well that they stand apart from the pack with these very high total scores. Other practices, at the lower end, like the Soil Carbon Amendment (e.g., Biochar, Compost, etc.), Nutrient Management, and Cover Crops, have smaller summed CPPE scores (25, 43, 44) as they are more specialized in addressing fewer resource concerns.

But what does it really mean that Tree/Shrub Establishment gets a score of 35 out of 55 total possible points for Soil, for instance? Let’s dig deeper.

Breaking Down the Points

To shed some light on what these numbers mean, in Table 2 we list out all the points Tree/Shrub Establishment gets for each of the 47 resource concerns. Is there a specific resource concern that interests you? Maybe “sediment transported to surface water” or “terrestrial habitat for wildlife”? You can go straight to those and see what scores this practice gets.

Highlights for Tree/Shrub Establishment:

Scores a 4 or a 5 for addressing over half the 11 Soil resource concerns – that’s impressive!

Provides a “substantial improvement” (score of 5) for three of the four Plant resource concerns: reducing plant pest pressure, improving plant productivity and health, and improving plant structure & composition.

Also scores a 4 in the Air Category for reducing greenhouse gases (GHGs), and a 5 in the Animal category for improving terrestrial habitat for wildlife & invertebrates.

In total: eight scores of 5 AND no negative numbers (recall that a zero (0) means there is no effect) generating the whopping 98 total CPPE points!

Curious how Prescribed Grazing and Conservation Cover stack up? Check out Tables 3 & 4.

Highlights for Prescribed Grazing:

Offers terrific solutions for eight of the 11 Soil resource concerns given the many 3 and 4 scores!

Does a solid job (3’s offer a “moderate improvement”) to addressing a few Water and Air concerns, like improving naturally available moisture use and reducing the transport of both sediment and pesticides to surface waters, and reducing particulate matter and GHG emissions.

Scores a 5 and a 4 in the Plant category for improving plant productivity & health and improving plant structure and composition (both super critical for grazing livestock!

Scores a 5 and a 4 in the Animal category for improving feed & forage imbalances and improving terrestrial habitat for wildlife and invertebrates.

In total: two scores of 5 and, just like Tree/Shrub Establishment, no negative numbers for an impressive 90 total CPPE points!

Highlights for Conservation Cover:

Multiple Soil resource concerns receive a 4-score, thus “moderate to substantial improvement,” could be expected for sheet and rill erosion, wind erosion, organic matter depletion, and aggregate stability.

While none of the three practices scored a 5 in the Water resource concerns, Conservation Cover received the highest overall water score and the most scores of 4: nutrients transported to surface water, nutrients transported to ground water, and sediment transported to surface water.

Conservation Cover gets the highest Air score out of these three practices, mainly due to scoring a 4 for both emissions of particulate matter and GHG emissions.

The Plant resource concerns are almost no match for conservation cover, offering a moderate to substantial improvement in three of four categories!

In total: no scores of 5, and no negative numbers, but a terrific 80 total CPPE points!

Policy Implications to Increase Adoption

While this offers an interesting look into the potential benefits these practices could offer, there are so many factors that influence the actual benefits when the practice is implemented. Below are three arenas that need continued investment and attention to increase adoption of these important practices.

1. Investing in Technical Assistance is Critical

The potential benefits are only realized when a practice is implemented and established properly. To do so, many different questions need to be considered by the farmer in collaboration with a conservation professional:

What farm-related natural resource concerns need treatment on the farm?

Which conservation practice is best designed to address which resource concern?

For tree/shrub establishment or conservation cover, what species of plants will thrive given the soils and climate to provide the desired outcome?

How large of a planting is needed to address resource concern?

Is there enough precipitation for the plants to thrive, or will irrigation be needed?

To maximize the benefits that can come from establishing these conservation practices, as well as others, questions like those above need to be thoughtfully considered. After all, just because Tree/Shrub Establishment gets a high CPPE rating doesn’t mean that every tree or shrub planted will necessarily positively impact every resource concerns. By ensuring farmers have an ample technical service network to select from - NRCS field staff, Soil and Water Conservation Districts, peer farmers, and/or qualified non-profit conservation organizations, Technical Service Providers (TSP), or private agricultural advisors - we can turn potential conservation benefits into realized outcomes.

This is why it’s so important to ensure there are adequate field staff in all these different public, private, and non-profit technical service offices, to continue robust funding for Conservation Technical Assistance through the annual appropriations process making its way through Congress right now. It is also why the transfer of the remaining Inflation Reduction Act conservation funding into the Farm Bill that was included in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act passed by Congress in July was so critical as these programs invest in both technical and financial assistance.

2. Investing in Financial Assistance

In our first article, we explored the economic benefits of “The Big 3”: Cover Crops, Nutrient Management, and Reduced Tillage or No-Till. These practices can often pay for themselves through cost decreases and potential yield improvements, though the economic outcome for cover crops can depend on adoption timeframe and integration with livestock. The three focus practices of this article, Tree/Shrub Establishment, Prescribed Grazing, and Conservation Cover, have fewer immediate economic benefits and can be very costly to implement.

According to a 2022 paper by Deutschman and Koep, the average Annual Useful Life Total Cost (lifetime cost of a practice, divided by the length of time it will be functional) of Conservation Cover and Prescribed Grazing is $11,092 and $12,393 per acre respectively (Tree/Shrub Establishment was not included in their analysis). Compare that to The Big 3, with annual averages of just $931 to $3,460 per acre, and it’s clear that financial assistance is needed if we want producers to take full advantage of Conservation Cover and Prescribed Grazing.

Unlike “The Big 3” that are annual management practices, Tree/Shrub Establishment and Conservation Cover are perennial practices that require long-term commitment. Practice lifespan is the minimum time the implemented practice is expected to be fully functional for its intended purposes. According to the National Handbook of Conservation Practices, while “The Big 3” and Prescribed Grazing have lifespans of just one year, Tree/Shrub Establishment has a 15-year lifespan and Conservation Cover has a 5-year lifespan.

Not only do these practices require one-time capital expenses associated with the planting, but there are also recurring maintenance costs to ensure the plants stay alive and grow for the requisite number of years to see the full benefits of these practices. That being said, Tom Rogers of Rogers Farm in California (see Photo 3 for an image of his almond orchard) found that Conservation Cover adds nitrogen to the soil and suppresses weed growth, saving him $100 per acre by using 56% less herbicide. This practice has been an adjustment for Rogers Farm, learning how to manage the cover with precisely timed mowing, but it makes economic sense.

Prescribed grazing, too, can require a substantial investment. In a 2019 article, Windh et al. calculated the total annual grazing system costs of various modeled scenarios, and found that rotational grazing had higher costs than continuous grazing systems. However in the Farmer’s Guide to Grazing on the Economic Considerations for Beef Producers, AFT reviewed five studies that reported higher net returns under intensive grazing; while producers may incur higher costs in the short run, intensive grazing may increase long-term economic performance. So while prescribed grazing is considered to have a one-year practice lifespan, a longer commitment to the practice can enable a producer to see an economic return.

Tree/Shrub Establishment, Prescribed Grazing, and Conservation Cover easily justify the need for public financial assistance support as they provide so much to society in the form of various environmental benefits, such as reducing erosion, reducing nutrients to surface waters, reducing plant pest pressure, and increasing terrestrial wildlife habitat.

As noted above, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB), signed into law on July 4, 2025, transfers all unobligated Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) conservation funds into the four key conservation programs, while simultaneously increasing permanent baseline funding for these same programs as follows:

Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) – $13.6 billion, a 36% increase

Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) – $31.55 billion, a 55% increase

Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) – $6.85 billion, a 26% increase

Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) – $4.475 billion, a 49% increase

We applaud the permanent increase in funding for these popular, oversubscribed programs that can incentivize the adoption of conservation practices, such as the three practices described above.

3. Investing in Research and Measurement to Build New Markets for Farmers

Realized outcomes are important for more than solely the ecological benefits we’ve focused on so far. If, for instance, a producer was interested in monetizing the environmental benefits generated from the adoption of their practices through ecosystem services markets (Heads up! This is what we’ll cover in our next article!), then the actual conservation outcomes are more important than the potential conservation benefits.

One of the first steps to participating in environmental markets involves measuring the environmental outcome. This was one of the original purposes of the PCSC projects, which were in the process of collecting data and designing new “climate-smart commodity” markets, when the PCSC program was replaced with the AMP initiative. All PCSC projects were required to measure and provide data on the carbon sequestered and greenhouse gas emissions lowered from the implementation of the practices on farms (measuring other environmental outcomes was optional). The goal was to build a database of valuable information that could help producers enter many different environmental markets.

We hope the critical work of data collection and conservation outcomes measurement will continue, including in AMP, so that producers can access these markets with confidence. We also hope the projects selected under the new AMP initiative recognize the many environmental and production benefits these three top CPPE-scoring practices have and continue to prioritize them in their outreach and educational efforts with farmers.